Seeing Old-Age as a Never-Ending Adventure

Share on social media

Ilse Telesmanich, 90, sprained her ankle hiking in South Africa last August. She tried to keep going on the three-week trip, she said, hobbled as she was. New York Times journalist, Kirk Johnson examines the trend towards older people becoming adventurers.

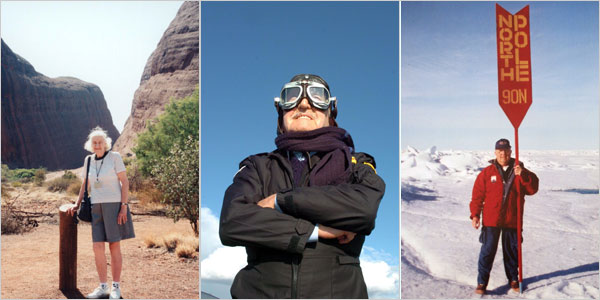

Ilse Telesmanich, 90, (left photo) sprained her ankle hiking in South Africa last August. She tried to keep going on the three-week trip, she said, hobbled as she was.

Ilse Telesmanich, 90, (left photo) sprained her ankle hiking in South Africa last August. She tried to keep going on the three-week trip, she said, hobbled as she was.

“I got very good at hopping on one foot the last time I sprained it,” she said.

But the guides had unfortunately failed to bring along any crutches — let alone walkers. So Ms. Telesmanich cut the trip short, but she is planning on leaving her home here in central Florida this summer to complete what she started.

Tom Lackey, 89, also continued to embrace adventure late into life, in his case as a way past the grief of losing his wife to a heart attack 10 years ago.

Mr. Lackey took up wing-walking. Last summer, he strapped his feet to the top of a single-engine biplane, like the daredevils of aviation’s early days, and flew across the English Channel at 160 miles per hour — with nothing between him and the wild blue yonder but goggles and layers of clothing to fight the wind-chill.

“My family thinks I’m mad,” Mr... Lackey said in a telephone interview discussing the flight — his 20th wing-walk. “I probably am.”

“My family thinks I’m mad,” Mr... Lackey said in a telephone interview discussing the flight — his 20th wing-walk. “I probably am.”

Intensely active older men and women who have the means and see the twilight years as just another stage of exploration are pushing further and harder, tossing aside presumed limitations. And the global travel and leisure industry, long focused on youth, is racing to keep up.

“This is an emerging market phenomenon based on tens of millions of longer-lived men and women with more youth vitality than ever imagined,” said Ken Dychtwald, a psychologist and author who has written widely about aging and economics.

And the so-called experiential marketplace - sensation, education, adventure and culture, estimated at $56 billion and growing, according to a new study from George Washington University - is where much of that new old-money is headed.

At the Grand Circle Corporation, for example, a Boston-based company that specializes in older travelers, adventure tours have gone from 16 percent of passenger volume in 2001 to 50 percent for advance bookings this year, even as the average traveler’s age has risen from 62 to 68.

At Exploritas, a nonprofit educational travel group previously known as Elderhostel, the proportion of people over 75 choosing adventure-tour options is up 27 percent since 2004. The sharpest growth has been in the over-85 crowd, more than 70 percent.

At VBT, a bike touring company in Vermont that does rides in countries around the world, the number of bikers over 70 has doubled in the last 10 years.

“Unusual is way more popular now,” said Alan E. Lewis, chairman of Grand Circle, “and with this audience, that’s a major shift.”

But the era of geriatric derring-do is also bringing new questions.

Take travel medical insurance. At InsureMyTrip.com, an online company, coverage that costs $15 for a 45-year-old runs four times that much or more for the same trip at age 85, and evacuation coverage for medical emergencies is not available at all through the company’s provider after that age.

Doctors are also struggling with new issues that uniquely affect many older travelers, like how to pack and protect medications that must be carried into the outback or the tundra without getting too hot, too cold, or lost.

“Everybody’s reading the handwriting on the wall,” said Dr. Jay Lemery, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital in Manhattan, which started one of the nation’s first fellowships a few years ago in trauma treatment for the active elderly.

Some pursue challenges close to home, mastering a headstand or the perfect side crane balance on a yoga mat. Others go far afield.

At Mount Everest Base Camp, in the Himalayas, for example, doctors at the medical tent now regularly see trekkers suffering from age-related maladies... But Dr. Eric L. Johnson, a physician in Idaho who has worked at Everest, also camped next to a 74-year-old woman who made it to 28,000 feet on the mountain, only about 1,000 feet from the summit, before she turned back.

Other experts in wilderness medicine say they think technology has diminished the perception of risk that, in past generations, might have kept people on the front porch.

“A leg fracture hiking the Inca Trail seems less frightening now, in the age of cellphones and satellite phones,” Dr. Lemery said. “So people go on these adventures and think, ‘I can get out of there if something goes wrong.’ ”

But some emergency medicine and rescue experts also say that older people might in fact be safer in adventurous, high-exertion activities and environments than their younger counterparts, or at least no less safe. And some use an old-fashioned word to explain why: wisdom.

“It’s still the same knuckleheads getting in trouble or coming unprepared; young people, mostly,” said Sgt. Bob Silva of the Eagle County Police Department in the central Colorado Rockies, who regularly gets called for search-and-rescue duty.

There is a certain pride of place that comes with age, too.

When Charles Smith, 89, a retired engineer from Delray Beach, Fla., was heading for the South Pole a few years ago, for example, a woman got off the plane at base camp and started bragging about being 80. She was quickly put in her place.

“One of the fellows in our group tapped her on the shoulder and said, ‘I don’t want to prick your balloon, but there are three in our group who are older,’ ” Mr. Smith said.

Sometimes, motivation strikes like lightning. After Betty Beauchemin’s husband died in 2006, she said, she just about shut down.

Then, one day in 2008 after attending a workshop on goal-setting near her home in Cranston, R.I., Ms. Beauchemin, 80, was sitting on a beach and had an inspiration: She wanted to go parasailing for the first time in her life — which she proceeded to do. That winter, she started skiing again.

Physiological luck plays a role, too. Ms. Telesmanich, whose sprained ankle has healed well, said she grew up athletic, playing sports with the boys, and never stopped.

For his part, Mr. Lackey, a retired builder in England, said he was preparing for his 90th birthday next May with an attempt to be the first person, of any age, to wing-walk both directions across the English Channel.

A friend from Mr. Lackey’s church, Sue Pitham, 49, said the first wing-walk seemed morbid to her, coming as it did from grief.

“I think the first one was a bit of a death wish, to be honest,” she said. “But then he realized he was an adrenaline junkie.”

Ms. Pitham said a stroke that Mr. Lackey suffered about six years ago slowed him down some, but not much. “He just needs a little more help getting on top of the plane now,” she said.

Photo credits: New York Times and Caters News/Bulls Press